Indigo dyeing (chàm) in Vietnam: a living tradition of ethnic communities

- on Jan 15, 2026 By: Trang Nhung NGUYEN

Before being a color, chàm, or traditional indigo dye, is a memory. A silent memory embedded in cotton fibers, passed down from generation to generation, worn on the body and lived daily by many Vietnamese ethnic groups. For French travelers in search of authenticity, chàm is not merely an aesthetic element: it is a gateway to a deeper understanding of rural, mountainous, and ancestral Vietnam.

In the north as well as in the center of the country, in remote valleys or on high plateaus, indigo blue still shapes everyday life. It clothes women, protects children, accompanies rituals, and affirms the identity of a people. In an era of textile globalization, this millennia-old tradition endures—fragile yet alive—carried by those who guard it: women.

What is chàm and where does indigo blue come from?

Chàm refers both to the dye plant and to the natural dyeing process used to obtain indigo blue. In Vietnam, this technique has been attested for centuries, long before the introduction of chemical dyes. It relies on the use of local plants, mainly from the Indigofera genus, cultivated or gathered in the wild.

Contrary to what one might think, blue does not exist directly in the plant. It emerges from a long process of transformation, fermentation, and oxidation. Chàm is therefore the result of a patient dialogue between humans, plants, water, and time.

Historically, this dye developed in Vietnam’s mountainous regions, where many ethnic minorities lived—and still live. Indigo blue prevailed for both practical and symbolic reasons. Durable, it protects fabrics against wear and insects. Symbolic, it evokes the earth, the sky, stability, and a sense of community belonging.

In traditional Vietnamese societies, wearing chàm is never a neutral act. The depth of the blue, its matte or shiny finish, tells a story: that of a village, an ethnic group, sometimes even a social status.

A long, demanding, and deeply ecological craft

Traditional indigo dyeing in Vietnam is a slow process requiring experience, intuition, and patience. Nothing is mechanized. Everything relies on observation and oral transmission.

The first step is harvesting chàm leaves. Depending on the region, plants are grown near homes or gathered in the wild. The leaves are then immersed in large jars filled with water, where they ferment for several days, sometimes several weeks. This fermentation gradually releases the pigment.

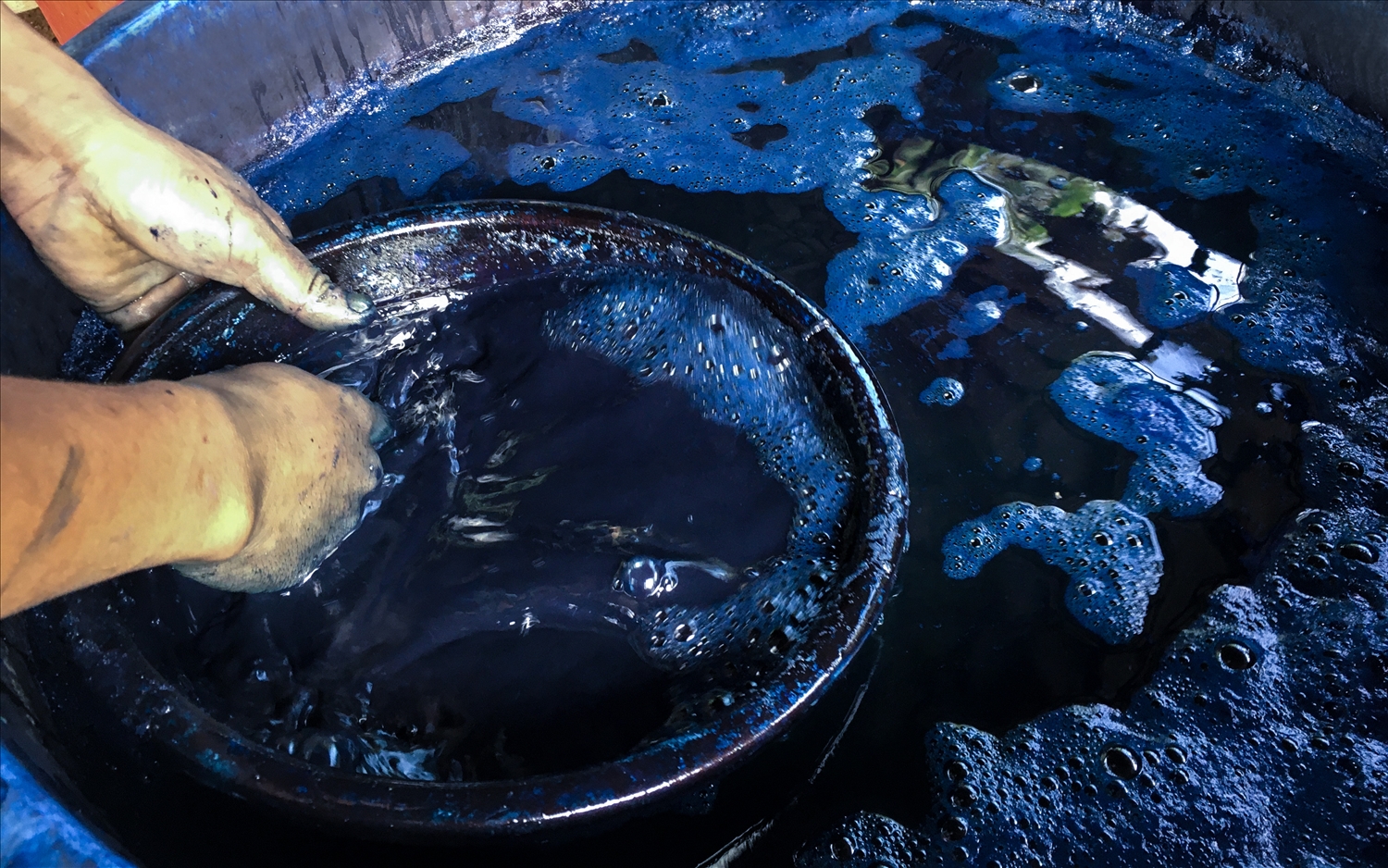

Once the liquid is ready, it is filtered and turned into a dye bath. The fabric—usually handwoven cotton or hemp—is then dipped, removed, wrung out, and exposed to the air. It is at this precise moment that the magic happens: upon contact with oxygen, the fabric shifts from a yellowish green to a deep blue.

This gesture is repeated many times. The more the fabric is dipped, the more intense the blue becomes. Some traditional garments require dozens of baths, spread over several weeks. Nothing is rushed. Time is an integral part of the color.

Finally, the fabric is washed, sometimes beaten or rubbed with wax or specific leaves to fix the dye and give it that characteristic matte, living appearance unique to chàm.

Indigo blue as a marker of cultural identity

In Vietnam, there is not one chàm, but many—just as many as there are ethnic groups and territories.

Among the Hmong, the blue is often very dark, almost black. The fabrics are thick and durable, sometimes decorated with wax-resist (batik) motifs before dyeing, creating subtle contrasts between blue and white. The garment thus becomes a true visual language.

The Dao, for their part, combine chàm with red and white embroidery, creating a strong and immediately recognizable aesthetic. Here, blue serves as a background, highlighting protective symbols hand-sewn onto the fabric.

Among the Tày and Nùng, the blue is softer and lighter. Clothing is sober and elegant, reflecting a worldview marked by balance and discretion.

Each technique, each shade, each motif tells a local story. It is this diversity that makes the richness of Vietnam’s textile heritage, to be explored more broadly through weaving and mountain culture.

Women, blue hands and living memory of chàm

In villages where traditional indigo dyeing is still practiced in Vietnam, chàm is above all a women’s story. For generations, it is they who have carried its knowledge, patience, and responsibility.

Women are the ones who plant chàm, watch over the growth of the leaves, observe the seasons and the land. They also prepare the dye baths, monitor fermentation, and adjust gestures according to the desired shade. Every movement is precise, learned through experience more than through words.

They are also the ones who sew and shape clothing for the entire family. From everyday garments to ceremonial attire, each piece is the result of long, often invisible, but essential work. Nothing is left to chance: the depth of the blue, the texture of the fabric, the strength of the seams.

Learning chàm begins very early. A young girl learns by watching her mother and grandmother. She observes, helps, repeats. Knowledge is not transmitted through books, but through the silent repetition of gestures, season after season.

Dyeing a fabric is never a purely utilitarian act. Chàm is prepared for festivals, major ceremonies, weddings, and moments that mark a life. Each indigo-dyed garment accompanies a passage, a transformation, a memory.

The hand of the woman who dyes the fabric is also the one that preserves the memory of an entire community.

Thus, through chàm, women do not merely pass on an artisanal technique. They preserve an identity, a social bond, and a continuity between generations.

Chàm, between ancestral heritage and contemporary aspirations

Today, chàm is not disappearing. It is transforming. It is finding new forms of expression in a world searching for meaning, slowness, and authenticity.

Indigo blue is reappearing in sustainable fashion, championed by designers sensitive to craftsmanship and natural materials. Chàm is no longer only traditional clothing: it becomes an ethical choice, a refusal of mass production, an affirmation of values.

In Vietnam’s mountainous regions, indigo dyeing is also at the heart of community-based tourism. Visitors no longer come only to admire a costume or buy a piece of fabric. They want to understand, see, touch, and experience.

Indigo dye workshops organized in villages allow travelers to follow every step of the process: harvesting leaves, immersing fabric, observing the transformation of color. This experience creates a direct connection between artisan and visitor, between tradition and modernity.

For many French travelers, chàm becomes a symbol—of a slower way of life, a respectful relationship with nature, a rediscovered sense of time. Wearing indigo fabric is no longer just about wearing a color: it is about carrying a story.

Thus, chàm now stands as an emblem of slow living, responsible fashion, and environmental respect. It reminds us that certain traditions, far from belonging to the past, still have much to say to the contemporary world.

Conclusion

Indigo dyeing in Vietnam is neither folkloric nor frozen in time. It is living, fragile, and deeply human. It tells the story of peoples who have learned to dialogue with nature, transform a plant into identity, and inscribe their memory into the very fabric of daily life.

For French travelers in search of meaning, chàm is an invitation to slow down, observe, and listen—an invitation to discover Vietnam beyond landscapes, through gestures, colors, and the women who safeguard them.

And it is often in this deep, imperfect, vibrant blue that Vietnam reveals its greatest authenticity.

Within the framework of a Vietnam journey focused on encounters and culture, discovering indigo dyeing offers insight into the contemporary challenges faced by Vietnamese ethnic groups, their customs, and their adaptation to the modern world.

Español

Español Français

Français

Timothy O Tool

on Feb 23, 2026Timothy William Groh

on Feb 23, 2026TwelmSC

on Feb 20, 2026Morgane Ter Cock

on Dec 18, 2025HerbertPhomaMS

on Oct 19, 2025